Introduction; Where Heaven Met the Delta

Sunday morning in a small wooden church deep in the Mississippi Delta. Sunlight streams through cracked stained glass, casting kaleidoscopes of color on worn pews. A preacher bellows from the pulpit, words heavy with fire and brimstone.

The preacher’s voice crescendos and then melts into song. The line between sermon and melody blurs into nothing. People sway, clap, and sing, their words a mix of praise and lament.

This is gospel blues (sometimes called Holy Blues) , a distinct musical form that emerged from African American spirituals and the lyrical, raw, and honest emotional storytelling of the blues. It is a melodic tapestry of praise and protest, joy and pain, faith and endurance.

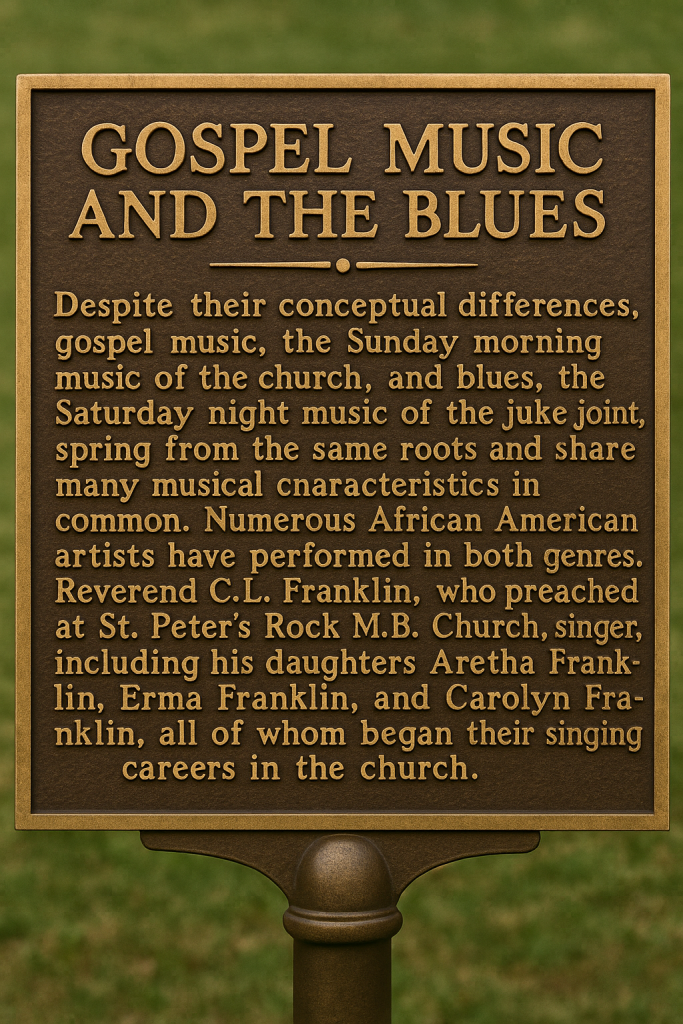

Gospel music and blues music have their origins in the same African American culture and history. The gospel speaks to the spiritual, while the blues deals with more earthly truths. But they share deep roots in the same fertile soil of pain and endurance, faith, and lived experience.

In this story, we will explore the origins of gospel blues and how they evolved from these shared cultural roots. We will meet the musical innovators that shaped the gospel blues sound, follow its musical journey, and see how the sound and spirit of gospel blues continue to influence music today.

However, we must first understand what gospel music means in the African American experience.

Roots of African American Religious Experience

Before gospel blues, black folks had been singing spirituals, work songs, and hymns for generations. Songs filled with messages of hope, struggle, and transcendence had ancient roots in African American history. Spirituals weren’t just music; they were lifelines, uniting people in shared belief and experience.

Central to this world was the church. Sunday services were multi-sensory, musical spectacles. Congregations sang call-and-response, clapped, and swayed in unison. This energy between preacher, choir, and churchgoers was the foundation of gospel blues’ passion.

African rhythmic traditions were reflected in these practices. Syncopated handclaps, layered beats, and the loose rhythms of work songs were all at play in church music. And field hollers, those long-drawn-out vocal calls sung by field workers, seeped into gospel melodies. These moody tones gave gospel blues its unique emotional punch.

Worship wasn’t remote or cerebral; it was a felt, embodied thing. Voices swelled and crashed like ocean waves, propelled by belief and human desire. Every note was a message, every rhythm connected to stories of survival in a harsh world. The marriage of holy lyrics and blues earthiness began here.

Gospel blues, then, was no sharp break from tradition. It was a continuation of these great African American music traditions. It carried on the storytelling legacy of spirituals, as well as the emotional reach of field songs. And the church provided fertile ground for all these elements to collide and coalesce into something both reverent and raw.

The church was where gospel blues began its journey, before spilling out of the pews and into the streets. And soon, those streets would lead to records.

The Birth of Gospel Blues in the Early 1900s

One of the key interactions was between rural blues and church music in the early 20th century. Blues music has its roots in field hollers, work songs, and spirituals, all of which were part of African American rural culture. These blues elements found their way into the African American church experience, particularly in holiness and Pentecostal churches.

Church services in these congregations were lively, often involving clapping, stomping, and even ecstatic expressions of faith. Many rural churches had relaxed their bans on instruments, so blues music often found a place in the mix. Guitars and harmonicas weren’t unusual, and blues rhythms could merge with religious lyrics.

Church elders were often suspicious of this merging of blues and gospel, fearing the worldly connotations of blues music and its expressions of sin and suffering. Many white preachers condemned “the devil’s music.” But the gospel message was still able to seep into the blues, leading to the development of gospel blues.

Songs might praise God in one verse and then express earthly concerns or complaints in the next, often with a raw emotional power. This blending of the sacred and the secular created a form of music that was both a personal and communal expression of faith, and a commentary on the hardships of daily life. It was as much a tool for survival as it was for salvation.

The fusion of blues and gospel traveled, from rural churches to urban areas, from revival tents to juke joints, by musicians who carried the melodies with them.

The people who played this music were as important to the spread of the genre as the music itself.

Pioneering Voices of Gospel Blues

Blind Willie Johnson’s vocals were coarse and impassioned. Tracks such as “Dark Was the Night Cold Was the Ground” were transcendental in their power and beauty.

A passionate preacher in sound and spirit, his slide guitar style elevated the lyrics and brought the gospel to life. Listeners experienced a profound sense of his faith.

The “Godmother of Rock and Roll,” Sister Rosetta Tharpe, was a fiery gospel singer with a style that was equally at home in churches and clubs.

Her approach to electric guitar was groundbreaking, fusing spiritual lyrics with a rollicking swing that influenced churchgoers and secular music lovers alike. She was a touchstone for later rock greats.

The Reverend Gary Davis had the fire of a faithful preacher in his shows. His incredible fingerpicking prowess wove ragtime, blues, and gospel in intricate patterns.

The sermons he spun on the strings of his guitar found audiences both on the street and in church pews, with Davis’s music serving as a ministry for many.

Blending the sacred message of gospel with the secular music of the blues, Johnson, Tharpe, and Davis changed the face of gospel music. The power and conviction of Johnson’s growl, Tharpe’s fearless showmanship, and Davis’s technical brilliance reached new audiences.

Blues musicians found new inspiration in the church, and gospel singers borrowed the emotion and authenticity of the blues feeling. Gospel blues recordings could now be heard in sanctuaries and honky tonks.

No longer just a Sunday morning music, gospel blues entered into the daily fabric of both sacred and secular life.

Gospel Blues in Worship and Popular Culture

Gospel blues music spread through tent revivals and lively church services. Preachers mixed fiery sermons with the songs. The congregations clapped and stomped, caught up in the fervor. It was a kind of worship that was both spiritual and intensely personal.

Radio broadcasts took gospel blues far beyond church pews. Rural stations would air programs of gospel blues. City listeners were introduced to this new style, characterized by its emotive vocals and calls for devotion. Many of these shows were live broadcasts, heightening the excitement.

Recordings also helped to spread gospel blues. Record labels sought out the power of artists like Blind Willie Johnson or Sister Rosetta Tharpe. Phonograph records could be shared easily, spreading gospel music across regions and social groups.

As years passed, gospel blues songs began to appear in secular venues as well. Community events, theaters, and even some nightclubs would feature gospel performances. The lyrics were often still spiritual, but the context also had more entertainment value.

This shift from church to stage was not without its controversy. Traditionalists feared the loss of the sacred message. Others felt it was a means to connect with broader audiences and preserve the tradition.

Gospel blues also began to exert an influence on mainstream blues.

Influence on Blues, Soul, and Rock

The influence of gospel blues on blues, soul, and rock was profound and enduring. Gospel blues set the standard for impassioned, emotive singing that later artists aspired to emulate. Singers learned the power of investing every note with their entire being.

The distinctive phrasing of gospel blues influenced soul icons like Sam Cooke and Aretha Franklin. Sam’s gospel-trained smoothness was evident in secular classics, while Aretha’s stirring renditions channeled the spirit of gospel.

Ray Charles bridged the gap between gospel and blues, infusing gospel chord progressions and inflections with the raw emotion of the blues. His music found a home both in churches and on jukeboxes, touching listeners of all faiths.

On guitar, elements of gospel blues infiltrated rock and roll. Guitarists incorporated syncopated riffs, call-and-response licks, and percussive strumming patterns into their playing, lending an electrifying, soulful edge to their sound.

In addition to vocal and guitar stylings, the overall structure of gospel blues songs left its mark on rock and soul music. Songs often built from a quiet beginning to an explosive, high-energy climax, a format many later hits adopted.

Even drummers and bass players were influenced by gospel blues. The rhythm section of gospel bands often focused on groove-based playing that testified with every beat. This rhythmic sensibility became a defining characteristic of countless soul and R&B recordings.

At its core, gospel blues wasn’t just about music; it was about conveying a message of strength, hope, and perseverance.

Themes of Faith, Struggle, and Redemption

Gospel blues lyrics were infused with themes of faith, struggle, and redemption.

Songs discussed hardship and suffering, but also a longing for spiritual salvation.

They were filled with the pain and hope of life’s journey, without forgetting the potential of a better future.

References to the Bible and the Exodus stories were standard, as listeners could see similarities in their own lives.

The story of Moses leading the Israelites out of Egypt became an allegory for the fight against segregation and injustice.

The lyrics gained historical and personal significance through these stories and allusions.

During times of poverty and segregation, gospel blues music provided strength and hope to listeners.

Churches, street corners, and community gatherings would resound with the sounds of gospel blues.

The songs would help people get through difficult times, providing comfort and reassurance.

Faith would help them remember that they could suffer and endure.

Hope was also very real and not only spiritual.

Songs could also be about the hope for freedom and justice in this life or the next.

Gospel blues music was a potent blend of hope, struggle, and redemption that resonated deeply with its listeners.

The power of gospel blues stemmed from the fusion of spiritual faith with the raw emotion of the blues.

Its followers could hear their lives reflected in the lyrics, but their burdens felt a little lighter in the sound.

Its message of faith, struggle, and redemption would continue to draw in more and more listeners.

Themes as strong as these would not allow gospel blues music to fade into obscurity-it would evolve.

Gospel Blues and the Modern Era

The gospel blues of the 1930s did not die out or disappear. The music lives on in contemporary singers and musicians. Taj Mahal is known for his roots blend of musical traditions, which include the warmer influence of gospel. The sacred steel guitar virtuoso Robert Randolph electrifies crowds with a spiritual focus. Shemekia Copeland’s gospel-influenced songs reflect the power of faith-led storytelling in today’s blues scene.

The festival circuit helps keep gospel blues alive. Annual events feature traditional gospel blues performances that feel as immediate as they do historic. In churches, gospel blues is often part of the Sunday program, serving as both a form of worship and a way to connect community members to each other. Grant-funded recording projects and small record labels with a focus on history are preserving these sounds.

The documentary form is a strong ally of the genre. Documentaries record the music, oral histories, and life experiences of gospel blues in films that are widely available to audiences far from its Southern birthplace. Streaming performances and videos on digital platforms create another form of availability, with the potential to reach global audiences in a matter of seconds.

Sharing music via social media platforms helps both legendary and up-and-coming artists to cultivate audiences beyond a geographical range.

Conclusion-Keeping the Spirit Alive

Gospel blues has been a unique fusion of spiritual fervor and earthly tribulation since its inception. Echoes of African spirituals and work songs found a new voice in the genre’s formation, rooted deeply in the rich soil of African American religious and musical tradition.

The duality of gospel blues is found in its ability to serve both the congregation and the secular listener. The rhythm and soul of gospel blues possess the power to raise a church to its feet, but also to calm the soul of a weary traveler in the dead of night.

By its very nature, gospel blues music was emotive and poignant, creating a legacy of emotional intensity in American music. The soul, R&B, and even rock music would later draw from the genre’s intense passion and moral overtones.

Gospel blues performance tradition today still reflects that juxtaposition of spirit and suffering. On stages, in churches, and across digital platforms, the music unites people through the common language of feeling and timeless truths.

Listen to gospel blues playlists that blend spiritual fervor with raw emotion.

Discover the pioneers of this genre and their stories for the next generation.

Support contemporary gospel blues artists, bridging heaven and earth with their music.