Introduction: The Heart of Delta Blues

The Mississippi Delta didn’t just give the world the blues; it gave the world a feeling. Blues music didn’t just grow in the Delta—it took root in fertile soil fed by desperation, endurance, and hope. In cotton fields and riverbanks and on dusty back roads, voices found expression in songs that spoke of hard times and fleeting moments of joy.

But the Delta blues were never monolithic. From one region of the Delta to the next, different subgenres took hold. They were shaped by local traditions, geography, and culture, music as much a product of the landscape as of heartbreak and travail.

Some styles were hard-edged and percussive. Others were slow and melancholy, rolling like the river. They wove together into a tapestry of sound that still echoes today.

In every song, riff, and footfall on a wood-plank porch, a story was being told. The Mississippi Delta didn’t just create blues musicians; it forged storytellers, pioneers, and icons.

In this post, we’ll explore some of the distinct subgenres that make up the Delta’s musical identity. From churning rhythms to spectral slide guitar, each has a history and a sound that’s worth a listen.

To appreciate the breadth and depth of the Delta blues, let’s start with a subgenre that’s defined by a driving, raw rhythm: Hill Country blues.

Hill Country Blues: Hyopnotic and Percussive

Hill Country blues originated in the hills of northern Mississippi, specifically in counties such as Tate, Lafayette, and Marshall. It’s a regional sound with deep roots and a rebellious edge. Hill Country doesn’t confine itself to the 12-bar structure like Delta blues.

Instead, the music locks into a steady, driving groove. Many songs revolve around a single chord, with the emphasis on rhythm and repetition. The effect is hypnotic, raw, and unfiltered, and endlessly compelling.

The guitar becomes a percussion instrument. The riffs are heavy, thumping like a heartbeat, propelling the song forward with gritty determination. Vocals often float over the beat, more like a chant than a melody, evoking incantations or declarations.

Artists like R.L. Burnside and Junior Kimbrough made this sound their own. Mississippi Fred McDowell added fire with his slide guitar, while staying true to tradition. Together, they defined a style that sounds both ancient and rebellious.

In the 1990s, Fat Possum Records helped revive the Hill Country blues movement, bringing it back into the spotlight. The recordings were lo-fi, but they didn’t try to sand off the edges. Instead, they celebrated the dirt and fire in the music. That authenticity resonated with fans of punk, garage, and indie rock.

Artists today continue to borrow their feel for live shows and lo-fi recordings. The influence of Hill Country blues can be heard in everything from Black Keys riffs to underground rock scenes. This is more than music; it’s movement, motion, and momentum.

Fans return to Hill Country blues for its trance-inducing power. It’s not polished, doesn’t try to be. It moves through the body, speaks to the bones, and won’t let go.

While Hill Country hypnotizes, the Bentonia blues tradition invites listeners into a darker, more introspective world.

Betonia Blues: Haunting and Eerie Tones

Bentonia, Mississippi, had a different blues tradition: haunting, hypnotic, and mysterious. It employed open minor tunings and modal, ethereal sounds that differed from other Delta styles. It sounds ghostly, even otherworldly.

The most famous practitioner was Skip James. His 1931 Paramount recordings, such as “Devil Got My Woman,” feature his distinctive falsetto and intricate fingerpicking. Nothing in his music is safe or sweet. It’s disquieting, yet utterly captivating.

The music itself is spectral, a slow and meditative growl. Bentonia blues doesn’t demand attention with volume or speed. It lingers in the background, then swells up on you. The lyrics often explore dark, supernatural subjects, and the harmonies lend it a haunting sound.

James’s friend and musical contemporary, Jack Owens, continued the tradition into the 1990s. Nowadays, Jimmy “Duck” Holmes is Bentonia’s living ambassador. He plays the music, educates audiences, and runs the Blue Front Café. It’s an unassuming little spot with a long history and rich blues tradition.

If you go to Bentonia, you don’t just hear the blues. You feel it. Bentonia Blues is raw, personal, and a direct link to the past. Each song is a conversation with history.

Bentonia may have whispered its blues, but in Clarksdale, the music roared—and so did the legends.

Clarksdale Blues: The Devil’s Crossroads

The Delta blues didn’t just happen; it was born in Clarksdale. This Mississippi crossroads is steeped in history, sweat, and six strings.

Here in the heart of the Delta, giants walked, legends lived, and myths were made. The soulful wails of Son House, the raw power of Muddy Waters, and the primal thump of Ike Turner gave the South its sound.

In Clarksdale, the blues are more than music—they’re folklore. Whispered tales of Johnny Law and deals with the devil in the nearby Crossroads infuse the town with a mysterious reverence.

Yet Clarksdale isn’t a shrine to the past. The blues are very much alive here. Drift through town, and you’ll hear blues coming out of car doors and through windows.

Visit the Delta Blues Museum to pay homage to the legends who made the blues what they are. Or catch some live tunes at Ground Zero Blues Club (owned in part by Morgan Freeman) for some true-blue soul.

Snap a photo at the Crossroads sign, where Robert Johnson supposedly made his deal. But the real show’s on the streets, where local musicians play for passion, not prestige.

The blues also have deep roots in Greenville, a little downriver from Clarksdale. Here, the music became smoother, more soulful.

Greenville Blues: Smooth and Soulful Sound

Greenville’s blues were smoother and soulful. It was on the Mississippi River and shared influences from jazz and early R&B.

It was less about hollers and shrieks, and more about warmth and clarity. Guitar work was more polished and less jagged.

Artists like Willie Love, Eddie Cusic, and Little Milton made music that sounded more polished. While it still expressed the blues of heartache and hard times, it was also a cleaner, more sophisticated sound.

Greenville’s juke joints provided the fertile ground for blues music to develop and change. Musicians could experiment in a variety of settings, adding elements of swing and gospel.

Greenville was also near Memphis and other larger urban areas, which allowed for music from Greenville to have a wider reach. Greenville was a hub, not just a pitstop.

Greenville’s music was in many ways a bridge between the down-home feeling and the more urbane sounds. It was a crucial part of where blues music was headed next.

Upriver from Greenville, Helena, Arkansas amplified Delta blues and helped spread it to new listeners.

Helena Blues: Arkansas Echo of the Delta

Though not in Mississippi, Helena, Arkansas, helped the blues reach wider ears. Its riverfront location drew countless musicians moving up and down the Delta.

Helena’s influence wasn’t just geographical. In 1941, the town launched something revolutionary—King Biscuit Time on KFFA radio. It became the South’s most important blues broadcast.

This daily show gave a platform to legends like Sonny Boy Williamson II and Robert Lockwood Jr. Through crackling speakers, the blues found its way into homes and hearts across the region.

Audiences heard electrified blues for the first time—raw, rhythmic, and unforgettable. It wasn’t polished. It was real.

As the signal traveled, so did inspiration. Young players learned licks straight from the airwaves, echoing them on porches, in clubs, and down dirt roads.

Helena didn’t just preserve the blues—it helped evolve it. The music gained volume, reach, and momentum.

To honor its musical roots, the King Biscuit Blues Festival began in 1986. Held annually, it draws fans worldwide to celebrate Helena’s deep connection to the blues.

That legacy lives on in each riff, each harmonica wail, and every foot tapping to the beat.

While Helena’s airwaves carried the blues, the signature sound of the Delta was still in the hands of one defining tool—the slide guitar.

Delta Slide Guitar Tradition

No sound evokes Delta blues like the bottleneck slide gliding across steel strings. It sings, cries, and growls—all in one breath.

This raw, expressive style gave the blues its voice. A simple slide turned a guitar into something human.

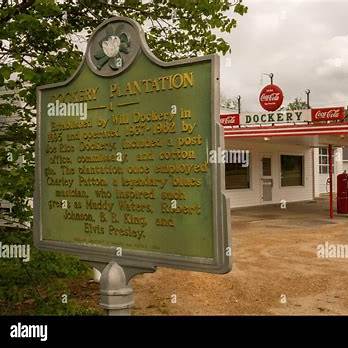

Early masters shaped this tradition from grit and creativity. Charley Patton scraped strings with steel blades. Bukka White used the neck of a broken bottle.

Son House struck his resonator guitar with pulsing rhythm and piercing slide tones. His playing danced between melody and percussion. It was primal, yet deeply emotional.

Slide guitar lets solo artists sound like entire bands. Each movement along the strings brought feeling, texture, and rhythm.

Mississippi Fred McDowell took that sound further. His confident, steady groove inspired future generations across genres.

Duane Allman, Bonnie Raitt, and Ry Cooder all borrowed from Delta slide players. The music spoke across time and place.

Even as the blues went electric, the slide remained. From Muddy Waters to Elmore James, its voice adapted but never lost its soul.

Slide guitar isn’t just a technique. It’s a mood, a memory, and a way of life in the Delta.

Passed down through records, stories, and front-porch lessons, this tradition still thrives today.

You can hear it in every moan of a steel string, every howl echoing off the levees.

However, not all Delta blues originated from cities or legends—some styles quietly echoed through the farmland of the Yazoo region.

Blues From the Yazoo Region

The Yazoo River basin was rich with deep country blues. This area, less commercially developed than Clarksdale or Greenville, nurtured a more rustic sound.

Musicians here often played on porches, in churches, or at informal gatherings. The vibe was unrefined, heartfelt, and steeped in the rhythms of daily life.

Artists like Hayes McMullan, Tommy Johnson, and Roosevelt Holts upheld a tradition of acoustic, rural storytelling. Their songs reflected field hollers, spirituals, and the struggle of labor under the Southern sun.

Unlike the polished blues from urban clubs, Yazoo blues stayed closer to its roots. The stories were personal. The delivery was direct.

Professional recording was rare for many of these players. Still, their songs traveled by word of mouth, by train, by memory.

The region’s isolation helped preserve older techniques and vocal styles. Bends, slurs, and modal tunings often gave the music a haunting edge.

Oral tradition kept the music alive. Fathers taught sons, neighbors shared licks, and songs evolved like spoken history.

In this fertile Delta soil, the blues remained raw and reflective. There was little flash, just feeling.

These local styles didn’t stay boxed in. As players moved and met, boundaries blurred, and the blues evolved.

Regional Fusion and Evolution

The Delta wasn’t just a birthplace—it was a living crossroads of musical exchange. Musicians moved by train, foot, or boat, spreading sounds and stories wherever they went. Each stop brought new rhythms, tunings, and techniques.

When Delta artists joined the Great Migration, they didn’t leave the blues behind. Instead, they carried it into cities like Chicago, St. Louis, and Detroit. Hill Country grooves fused with electric guitar riffs. Bentonia’s eerie tunings met modern bands and studios.

This journey didn’t wipe away regional styles—it reshaped them. Raw Delta energy gave rise to Chicago’s urban stomp. Texas blues added flash. Even British rockers borrowed Delta phrasing and grit.

By the 1960s, revivalists began to dig deeper. Young players and scholars unearthed recordings, visited surviving legends, and reignited interest in local traditions. The early 2000s brought another wave—this time with digital tools, indie labels, and global audiences.

Festivals like the Juke Joint Festival in Clarksdale or Bentonia Blues Festival keep local flavors alive. Record labels, documentaries, and podcasts now carry these stories worldwide. A field holler from Mississippi might now echo on a global stage.

Importantly, this evolution isn’t just musical—it’s cultural. Communities still gather in juke joints, cafés, and porches, sharing songs as living history. Blues remains a conversation between past and present.

Even now, the fingerprints of each subregion remain visible in today’s music—and in the communities that preserve them.

Conclusion: A Rich Patchwork of Blues

Delta blues isn’t just one sound—it’s a patchwork of voices shaped by land, life, and longing.

Each region added something distinct to the mix.

The Hill Country stomped with rhythm. Bentonia whispered with eerie calm. Clarksdale burned with fiery passion. Greenville brought smooth polish. Helena, though across the river, gave the blues wings.

These styles didn’t vanish—they evolved. You’ll find them in juke joints, front porches, blues cafés, museums, and annual festivals. Each keeps the flame burning bright.

Modern musicians honor these roots. They blend tradition with fresh ideas, creating new expressions that echo the past while speaking to today.

Whether you’re a lifelong fan or just discovering the genre, regional Delta blues opens the door to its beating heart.