Introduction: A Smooth Sound in a Gritty World

Late 1940s, Los Angeles. A smoky nightclub throbs with hushed anticipation. Curtains are drawn, and cigarette smoke wafts through the air. A scent of whiskey lingers, almost spiritual.

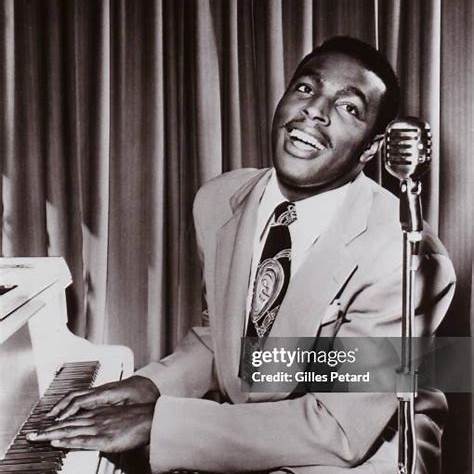

Spotlight. A man in a chair is seated at the piano. Elegant fingers dance over the keys. A voice, rich, smooth, and sultry, oozes over the crowd.

It was the voice of Charles Brown. A singer and pianist who told stories with his songs. Painting vivid pictures of love, desire, and loneliness.

Brown was a central figure in the post-war blues and R&B scene. His music was sophisticated and emotionally profound.

His blend of smoothness and soulfulness helped define the West Coast blues sound—a smoother, less gritty style than its Delta or Chicago relatives, but no less profound.

The lyrics were understated, and the notes were chosen with precision. Brown’s shows were a musical dialogue, a personal and poignant conversation.

In a world trying to recover from war, trying to find some relief and solace, his voice was a welcome balm—smooth piano lines like a gently flowing stream beneath dark, brooding clouds.

Brown’s life and music encapsulated the contrasts of West Coast blues. Smooth yet still rough around the edges, elegant but still hardened by life.

To understand how Charles Brown was called the “gentleman of the blues,” we have to start at the beginning. Brown was born in Texas.

From Texas Roots to California Dreams

On September 13, 1922, Charles Brown was born in Texas City, Texas. Gospel music, spirituals, and the blues were the sounds of his youth. These were the sounds that first captivated his attention and inspired him to fall in love with music. Growing up in Texas City, Brown was exposed to a rich musical environment, which greatly influenced his later work.

Brown was a student of classical piano from a young age. He was not like many bluesmen of the time, who often learned their craft by ear. He honed his skills on the piano, learning to read music and play with a deft touch. This level of musicianship would become a defining feature of his playing.

Before his music career, Brown attended Prairie View A&M to study chemistry. He had a degree in science, but he was also an avid pianist. As World War II raged, many African American workers migrated to California. There were jobs in the state’s defense industry. California also had a lively nightlife and an emerging music scene. While the jobs drew Black workers to California, the culture they left behind also had a magnetic effect on the workers. The clubs in places like Los Angeles and Oakland were filled with the sounds of jazz, jump blues, and a new R&B music style.

In the mid-1940s, Brown moved to Los Angeles. The city was alive with music, and Brown began to make a name for himself. He spent many nights playing in clubs and honky-tonks, and his smooth playing quickly gained him a following. Late-night jam sessions and crowded dance floors became a routine for Brown. He was working toward a life in music in the clubs of Los Angeles.

Brown was soon lured to California, where he found opportunity. In a time when blues music was gaining popularity, an intense club scene in California was in high demand for blues acts. The club scene was growing in places like Los Angeles and Oakland. The question was, where could Brown make a career?

In an instance of great fortune, Brown found himself with an opportunity to join a group that was already popular.

Johnny Moore’s Three Blazers

Johnny Moore’s Three Blazers formed in the early 1940s. Guitarist Johnny Moore, pianist/vocalist Charles Brown, and bassist Eddie Williams made up the core trio. Their polished, easygoing style was a hit in small clubs and cocktail lounges.

The Three Blazers focused on subtlety. Brown’s smooth baritone and gentle piano rhythms blended with Moore’s understated guitar riffs and Williams’s solid bass lines. Their urbane, refined sound was a contrast to rougher, more intense blues.

However, in 1945, “Driftin’ Blues” catapulted them to stardom. Brown’s ethereal, wistful vocal performance on the song touched a nerve with Black and white audiences alike. It became a prominent R&B hit, spending months at the top of the charts.

Both Black and white fans showed up to see the Blazers in action. The trio’s stylish, emotional approach made them a favorite in Los Angeles and helped popularize West Coast blues. Their smooth, cosmopolitan sound would influence generations of musicians.

Touring the U.S., the Blazers recorded many classic sides. Each new release highlighted Brown’s storytelling and the group’s cohesive sound. The Three Blazers became a template for mixing blues authenticity with a nightclub aesthetic.

The Three Blazers were a launching pad for Brown’s solo career. However, his solo work would make him a blues legend.

Solo Stardom and Signature Songs

Charles Brown split from Johnny Moore’s Three Blazers in the late 1940s.

It was a fresh start that would shape his legacy to come.

Signing with Aladdin Records, Brown was determined to show that he could carry a show on his own.

His silky voice and laid-back piano were well-suited to post-war America’s burgeoning R&B scene.

In 1947, he recorded “Merry Christmas Baby,” a warm, bluesy holiday classic.

The song would become an annual radio favorite, playing in the streets and on the airwaves every December for years to come.

Then there was “Trouble Blues” in 1950, a slow-burning R&B chart-topper.

Its bluesy melancholy and heartfelt performance spoke to anyone who’d ever been on the receiving end of a broken heart.

Arguably his most chillingly beautiful, “Black Night” depicted a forlorn emptiness in deep, moody tones.

Each line dripped with a sense of resignation, the piano line like a distant drumbeat calling out into the night.

Brown’s approach to singing was subtle and understated.

There was no screaming or bellowing—just a gentle, nearly conversational delivery that coaxed you into closer, like old friends swapping stories over drinks in the early hours.

At the piano, his left hand left much more space than was typical, providing simple bass lines.

His right hand was light and nimble, making use of jazzy chords.

On stage, Brown presented an image of sophisticated style.

Tailored suits and well-groomed, an easygoing elegance that matched the smoothness of his playing.

It was as much a part of his performance as the songs.

He carried himself not only as a blues musician but as a gentleman of the genre.

His solo hits and signature style spoke for themselves.

Brown didn’t need to be part of a band to leave his mark.

The intimacy of his music, the quiet grace of his performance stood out against louder, more flamboyant acts of his era.

His songs seemed to hang in the air long after they were over, like the scent of perfume in a once-lived-in room.

And in the silence that remained, his voice seemed to be there still, present and patient and impossible to forget.

Brown’s sound wasn’t just his own—it was part of a wider movement that defined the West Coast blues identity.

The West Coast Blues Sound

Developed in the post-war era, West Coast blues was more polished and urbane than many of its predecessors. Jazz influences, smooth arrangements, and swinging rhythms characterized the music. Listeners were treated to sophisticated horn lines, swinging rhythms, and an overall vibe that could be called urbane.

The influence of big-band jazz was powerful. Lush, horn arrangements and staid soloing complemented a steady swing groove from the rhythm section. It sounded at home both in the cocktail lounge and a raucous dance hall.

Guitarists such as T-Bone Walker, Amos Milburn, and Pee Wee Crayton added bluesy phrasing and high levels of musicianship. Milburn’s rollicking piano and party-ready lyrics, along with Crayton’s biting guitar tone, are both cloaked in an aura of urbane cool.

This sound was distinctly different from other popular regional blues sounds. Delta blues continued to be raw and rural. Chicago blues took the emotional intensity of Delta blues and electrified it, resulting in a rougher, more distorted sound. West Coast blues, by contrast, was smooth and often possessed a cinematic quality.

Charles Brown was an exception to many of the smooth urban conventions. With his romantic and intimate approach, each song felt like a love letter to the listener. His subtle phrasing and restrained piano style were like an aural whispered confession.

Yet, even for a smooth urban star like Brown, the times were changing – and not necessarily to his benefit.

Decline, Rediscovery, and Resurgance

The music industry was undergoing significant changes in the 1960s. Rock ’n’ roll, soul, and other new styles were taking the public in new directions, and smooth musicians like Brown had to work harder for their share of attention.

British Invasion groups and Motown acts were major sellers, while his single releases were largely unsuccessful. Radio and television gave him less exposure, and his national reputation waned. He continued to tour and was still popular in his home region.

In the 1970s, Brown played clubs and small halls, continuing to share his music with audiences. While he remained an elegant performer with his piano and voice, without national exposure, he was less visible. Fans who heard him were glad to do so.

The 1980s saw a blues revival, and Brown began to gain notice from new audiences. Festival appearances, television guest spots, and a European tour made him more visible again. Younger artists who admired his touch and tone reached out to him, and Bonnie Raitt was one of Brown’s most enthusiastic supporters.

In the 1990s, Brown was nominated for Grammy awards and received national recognition. His performances in his later years showed that his music had only improved with time. Warm, rich, and flavorful, his shows were an added treat for those who could hear them.

The revival was as much about recognition for Brown’s influence on the American music scene as it was about nostalgia.

Influence and Legacy

Charles Brown’s silky voice influenced many vocalists. Ray Charles absorbed his phrasing, and Nat King Cole-styled singers emulated his romantic, conversational crooning.

He influenced West Coast R&B and early soul music. His relaxed swing, sophisticated arrangements, and intimate, storytelling style became a template for singers who wanted to swing with class.

Brown was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame in 1996 and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1999.

“Merry Christmas Baby” became a holiday blues standard. New listeners discover the song each December and hear Brown’s warm, understated vocal style.

Singers in blues and jazz continue to steal his unflashy piano-playing and laid-back vocal phrasing. His influence sneaks into their shows without the big production.

Brown’s music lives on for new fans who discover him. He died in 1999, but his voice endures.

Conclusion: Keeping Charles Brown’s Voice Alive

Charles Brown’s music career, from his humble beginnings in Texas to his major successes on the California scene, helped develop the sound of West Coast blues. His velvet voice effortlessly spanned jazz, blues, and the earliest forms of soul.

Audiences are still seduced by the sounds of “Driftin’ Blues” and “Black Night” the way that they were back in the 1940s. His musical legacy spans across both generations and genre divides.

Stream “Driftin’ Blues” or “Black Night” tonight.

Introduce his music to new audiences with young listeners in mind.

Learn about the history of the blues and support current artists keeping his legacy alive.

The smooth, velvet tones of Charles Brown’s voice live on in every note of the West Coast blues sound.