Introduction: A New Sound Fron Across the Pond

Muddy Waters plugged his electric guitar in, and British teens did not just listen, they aligned their entire lives to the blues.

This was more than a show. This was a creative lightning strike across the pond.

British musicians raised on skiffle and swing heard the raw soul of American blues. They didn’t just love it; they learned it, lived it, and made it their own. Blues records from Chess and Vee-Jay became gospel in smoky flats and basement clubs.

It was called the British Blues Revival—a burning, heart-on-sleeve rediscovery of a music long ignored in its homeland. Alexis Korner, John Mayall, Cyril Davies, and others were at the forefront of the movement. It wasn’t a flash in the pan; it was a full-on cultural revival.

The Rolling Stones, The Yardbirds, and Cream took it all back to America in short order. Kids who had only known R&B as imitated by white boys now saw it being covered in new ways by those white boys who were covering those original black artists.

This is not a story of stolen music.

This is the story of its rebirth, reinvention, and return.

Before it made its way back across the Atlantic, it had to hit home in Britain.

Why Britain Fell in Love With American Blues

Britain in the 1950s was a drab place. War, rationing, and a lacklustre culture of smooth pop music didn’t offer teenagers much to get excited about.

Things got a whole lot better with the blues. A culture of violence, woe, and raw power smuggled in on wax from across the Atlantic didn’t just sound great; it mattered.

A young British audience wanted more. The blues of Chess Records and other American labels spoke to them; the sound of Muddy Waters and Robert Johnson was pure truth.

Add in a wave of skiffle – Led Zeppelin frontman Robert Plant, particularly drawn to the raw approach of Lonnie Donegan and his mix of American folk and blues tunes – and young people in the UK took to it with their homemade guitars and with a shiny washboard in hand.

Then came the moment that changed everything. British blues guitarists and others flocked to see Big Bill Broonzy when he toured Britain in 1958. His “burning, whisky-soaked bass-baritone” sent shockwaves through his audience, many of whom had never seen an African American artist in the flesh.

It was the blues, and it was rebellion condensed into twelve bars of hard truth that resonated with a country full of restless youth.

They watched. They listened. And they picked up a guitar and started to play.

The first wave of British blues musicians followed.

Key British Pioneers of the Blues Boom

Britain needed a catalyst, and Alexis Korner was the spark. He and Cyril Davies formed Blues Incorporated, Britain’s first electric blues band, and they meant business.

These cats weren’t slapping on the blackface to laugh. This was pure, raunchy, back-alley, Delta music that had found its way across the ocean.

Musicians were queuing up in smoky clubs to check out these young fellas, inspired by what they were doing, chomping at the bit to get in there themselves and give it a whirl.

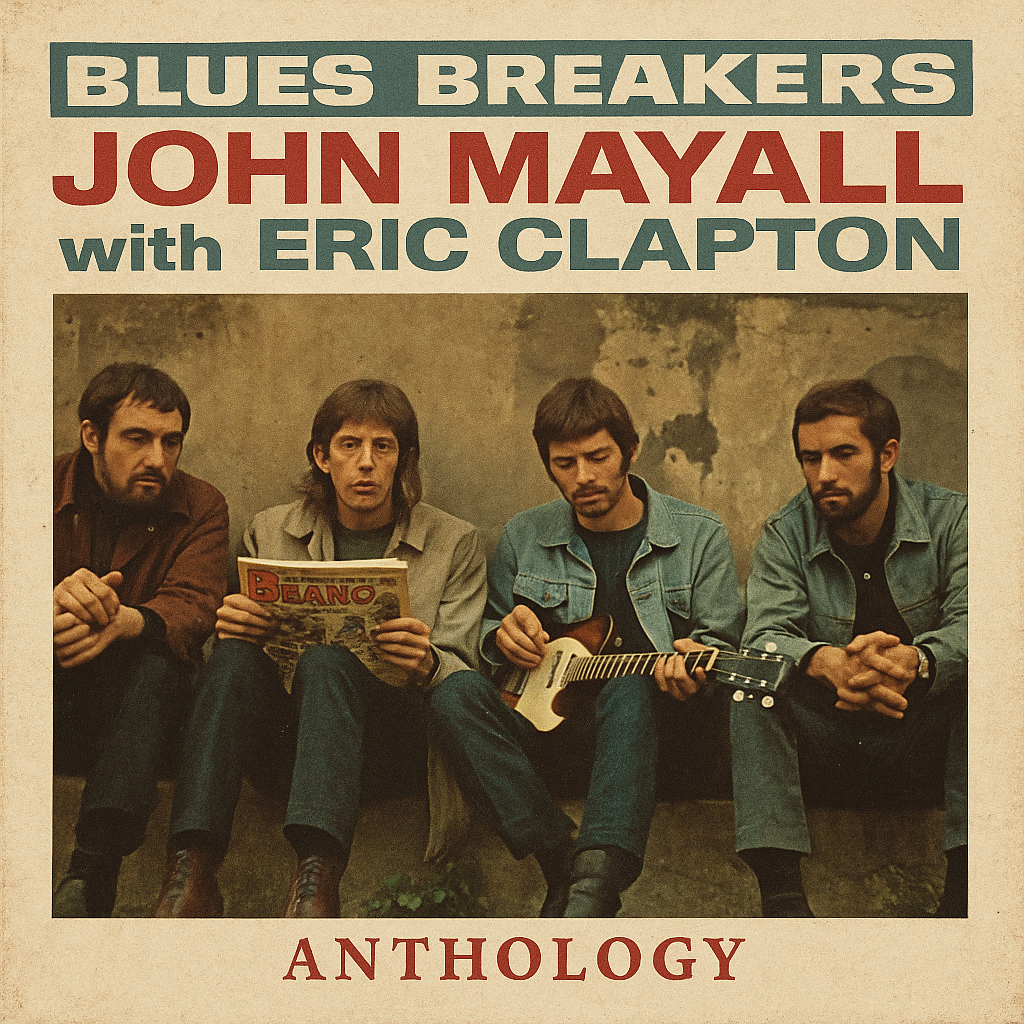

One of those wide-eyed aficionados was John Mayall, a true believer. With the Bluesbreakers, he provided a launching pad for his disciples, and they came and went, sharper and bolder and better than ever at the blues.

Eric Clapton came and went. So did Peter Green, Mick Taylor, and Jack Bruce. Each man added to Mayall’s reputation and the development of blues music in their unique ways.

And other names were starting to percolate. Mick Jagger and Keith Richards met and shared a love for the music of Chuck Berry and Muddy Waters. Jimmy Page was also working on these blues riffs that would one day blow up stadiums.

They were young and hungry, plugged into the sound of American blues and fired by the chance to make their statements. But this was not mimicry.

British blues was more than just a tribute act. It was a phenomenon, with its dynamic energy.

Still, the influences were always apparent. Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, and Elmore James would always be staples on their turntables. Reverence was the very thing that incited their rebellion, and the music continued to develop.

But once the ball had started to roll, it was only a matter of time before the ripples of this renaissance made it back to the source.

How the Music Traveled Back Over the Atlantic

The Rolling Stones ignited a cultural revival with their 1964 U.S. tour. Americans were shocked. A group of teenage English musicians was resuscitating music that seemed raw and dangerous.

They weren’t embarrassed about their sources either. In their performances and interviews, they raved about Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, and Willie Dixon. They weren’t stealing from them. The Stones and their new British cohorts idolized them.

Songs of the blues masters returned to American radio, reinterpreted through British amplification and a revitalized energy. Young Americans began searching for the original recordings. Record stores undusted long-neglected albums and reissued them.

Old blues albums began to sell rapidly, and names such as Robert Johnson and Lead Belly started to reach new audiences. The British invasion reintroduced the country to its history.

And even better, many of the legends they were emulating were coaxed back into performing. Clubs and concert festivals began booking bluesmen. Artists such as B.B. King, John Lee Hooker, and Muddy Waters found new audiences.

Some made new albums with younger rock musicians often backing them. This cross-pollination of artists blended the integrity of the past with the passion of rock and roll.

Included among those reintroducing this music were a few whose names will forever be linked with rock royalThe Rolling Stones.

The Rolling Stones, Clapton and the Blues Explosion

British bands didn’t simply adore the blues, they amplified it. The Rolling Stones took raw American blues and presented it to screaming teenage audiences across the globe. The band covered Slim Harpo, Willie Dixon, Muddy Waters, and others with a fervor that was both reverent and energetic.

It was no secret that the band members loved the blues. The band took their name from a Muddy Waters song. The group frequently mentioned their blues influences in interviews and album liner notes.

Eric Clapton treated the blues like sacred text. Robert Johnson was his Bible, and Clapton’s playing was a synthesis of virtuosity and deep, emotional reverence for those older Delta recordings.

Cream amped the blues up to an ungodly volume. The three piece took improvisation and sheer volume to previously unheard levels. The emotion, though, was still there. Raw, wailing, and unmistakably the blues.

Led Zeppelin and Fleetwood Mac brought in new influences, a hard rock swagger and psychedelic flourishes. The blues was still there, though, pulsing beneath the fuzz and showmanship.

Every guitar riff, no matter how overdriven, harkened back to the Mississippi Delta and Chicago clubs. British musicians were proud of that lineage. They proudly proclaimed it, in homage to the bands that inspired them.

This new movement was not simply a stylistic appropriation, it was an act of homage. An act of homage that introduced millions of fans to forgotten names and songs

The Impact on American Artists and Audiences

But the blues were also about to reach a new peak.

As interest in blues grew in the UK, the legends of the past were reissued for American consumption. Their fans rediscovered a music they’d previously dismissed – now filtered through British mouths and distorted guitars.

The revivalists brought the elders back to Europe. Blues festivals and the American Folk Blues Festival tour, in particular, were a second (maybe even third) wind for the greats.

Audiences flocked to Howlin’ Wolf, Sonny Boy Williamson, Memphis Slim, Sonny Boy Nelson, Champion Jack Dupree, and a host of others.

In America, the classic bluesmen started to be feted on stage with the new British fans. Eric Clapton jammed with Freddie King; the Rolling Stones brought many of their heroes on tour with them.

It was a chance for the older generation to make a few extra bucks – as well as to relive the glory days. A second chance to bask in the adulation, with fans too young to have seen them the first time around.

Younger American listeners started turning back to the music. The British bands had reconnected them with the music of the old masters. With time and space to explore, their interest in the original versions of those songs began to deepen.

Radio stations started playing the old tracks again. Record shops restocked John Lee Hooker, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Elmore James, and Big Mama Thornton.

The excitement of the original blues scenes in the States was about to return. Just in time to find their heroes, many of whom had been forgotten or neglected, finally received the accolades they so richly deserved.

The blues had come home, more appreciated and revered than ever.

The British blues boom was not without its detractors, however.

Criticism and Controversy: Cultural Borrowing or Tribute?

Criticism soon followed the British blues boom. Some listeners felt the movement borrowed too heavily from music rooted in Black struggle, history, and resilience.

The charge wasn’t subtle—British bands made millions playing sounds born from poverty and oppression. Many original blues musicians never received fair royalties or widespread recognition.

Still, not all views were harsh. Artists like Eric Clapton and the Rolling Stones often named their influences publicly and shared stages with their heroes.

They didn’t just cover songs—they celebrated them, helping introduce blues pioneers to new, eager fans across the globe. In many ways, their fame amplified the voices of those who had been forgotten.

At the same time, deeper discussions began. The revival forced audiences to ask who gets credit, who gets paid, and who tells the story.

It stirred hard truths, but also opened doors. The music brought people together, but it also demanded honest reflection on its origins.

Despite controversy, the revival left a lasting mark not only in America but around the world.

Legacy: A Global Blues Movement Emerges

The music that took root in American juke joints was transplanted and cultivated overseas.

British blues had reinvigorated interest in the blues in Europe, Japan, and even Australia.

In short order, foreign listeners and players made the music their own, studying, performing, and developing whole new scenes. As they did, original voices from these various corners of the world began to emerge. While steeped in the past, these musicians were creating something new.

If the modern-day blues festivals in Tokyo and Norway exist, it’s because the blues revival happened. It set into motion the wheel of a global party that celebrated pure, emotive music.

Musicians today will still nod to those American masters, the originators, as well as the British music makers who helped put it all on the map.

Blues is a language that tells a story of feeling and rhythm, of heartbreak and determination. It has become a dialect that is understood worldwide, reaching far beyond either Mississippi or London.

That’s the enduring impact, and with that thought in mind, we’ll leave you with one final consideration of how much history this revival changed.

Conlusion: How the Revival Changed Everything

The British Blues Revival did not so much copy as rekindle the spirit of the original. A spark that became a cultural wildfire. Songs reborn, and forgotten legends once more on stage.

It redefined American music, striking a balance between reverence for the past and a reimagining for the future. The Blues transcended as timeless, global, and deeply personal.

🎧 Listen to a British blues playlist. Experience the music’s transformation.

📚 Share the stories of the players who gave it their souls.

🎸 Support today’s artists, and pass it forward to the next generation.